With Nelson to Bastia 1794

Article by George Cattermole

A Lancashire Infantry Museum Narrative History

A casual passer-by crossing Trafalgar Square in late October, in any year, might stop to examine the wreaths laid beneath Nelson’s Column during the annual Trafalgar Day parade. Amongst the mainly Naval wreaths he may wonder at the relevance of one bearing the badge of an Army Regiment, namelyThe Duke of Lancaster’s Regiment, emblazoned on a blue riband, with the single word ‘Bastia’ and the date 1794.

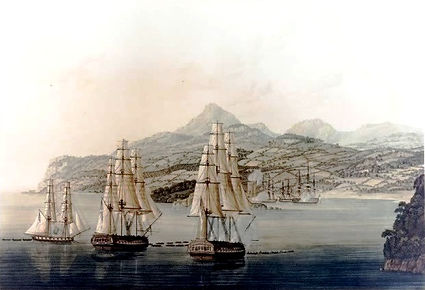

Early in the French Revolutionary Wars, having failed to help the Royalists defend Toulon from the French Revolutionary Republicans, the British fleet under Admiral Lord Hood sailed for Corsica, where a nationalist uprising had confined the revolutionary garrison to coastal enclaves around Bastia, Calvi and San Fiorenzo (now St. Florent).

The British Fleet off Corsica in 1794

By 7 February 1794, the British invasion force was off Mortello Point, where a solid masonry tower mounting 18- pounder guns barred access to the Gulf of San Fiorenzo, the planned base for future operations. This formidable defence work, after which the later Martello Towers on England’s coasts were named, was the first of several strong points which had to be taken before the British Fleet could enter the Gulf. That day, a force of 600 infantry, including detachments of the 30th Foot (later 1st East Lancashires), under Major General Dundas, the military Commander, landed and occupied heights overlooking the Mortello tower.

The Tower was unsuccessfully bombarded by two British warships, one of which was forced to haul out of gunshot range, with over 60 casualties and on fire. Ashore British 6- pounder field guns were equally impotent. Finally, an 18-pounder from HMS Victory was brought ashore and sited 150 yards from the tower. It still took two days of battering with hot shot, while the infantry kept up a steady fire to keep the defenders heads down, before the tower surrendered.

The Mortella Tower, sketched by British officer

Successful assaults were then made on other objectives in the Gulf of San Fiorenzo. Using pulleys and sledges, British sailors valiantly hauled six 42-hundred weight cannon 700 feet above sea level to mount a two-day bombardment. This was followed by a silent infantry night attack which routed the French garrison who lost 175 men out of 500. A detachment from the 30th under Lieutenant Ian Hamilton lost one sergeant killed and two men wounded. The French then abandoned the remaining batteries around the gulf and the strongly held fortified town of San Fiorenzo and withdrew across the mountains to Bastia, then the capital of the island.

Hood now had his secure anchorage and base for future operations. But Dundas, the military commander, advised that Bastia could not be taken by his little force and recommended a blockade. This unwelcome counsel did not accord with Hood’s requirement for a glorious victory to redeem his failure at Toulon, and it fortified the resolutely ill-humoured old admiral’s prejudice against military men. Piqued, he re-embarked the detachments of the 11th, 25th, 30th and 69th Regiments who, as marines, were under his command.

He then appointed Captain Horatio Nelson, of HMS Agamemnon, to take Bastia with a mixed force of seamen and marines, including the detachments of the 30th. The force of 1248 officers and men landed on the evening of 4 April, with Lt Col William Vilettes of the 69th in command and Major Robert Brereton of the 30th as second in command.

Private soldier and officer of the 30th, 1793.

The massive citadel of Bastia, crouched on a rock overlooking the sea, was more strongly defended than either Dundas or Hood had imagined; and Nelson, having intercepted French dispatches, was uncomfortably aware that the French garrison outnumbered the besiegers by at least three to one. The ambitious and almost absurdly confident young captain kept this intelligence to himself for fear of losing an opportunity for personal distinction.

Indeed, in their heroic ignorance of land operations both Hood and Nelson seemed to equate the reduction of a major fortress with laying alongside an enemy man-of-war. On 4 April Hood wrote, with quite unfounded optimism, that he expected the batteries to open within 48 hours and for Bastia to be reduced in ten days, while Nelson recklessly boasted that, ‘It was I who, knowing that the force in Bastia to be upwards of four thousand men, as I have now only ventured to tell Lord Hood, landed with only twelve hundred men, and kept the secret to within this week past’

The troops and seamen toiled for a week in foul weather, and by 11 April Nelson had established a battery on a ridge 1,600 yards from the citadel; eight 8-pounders from HMS Agamemnon and eight 13-inch mortars. Hood summoned the town to surrender.

‘I have hot shot for your ships and bayonets for your troops,’ came the defiant reply. ‘When two thirds of our men are killed, I will then trust to the generosity of the English’.

At this Nelson’s guns opened fire and HMS Prosélyte was ordered inshore as a floating battery. This vessel, a frigate-bomb taken at Toulon, had on board a party of the 30th who had no doubt been trained to man the 12-pounder guns.

Caught by an awkward swell as she anchored, Prosélyte became exposed to heavy fire of red-hot shot which lodged among flammable material in the hold and the ship was soon ablaze. The distress signal was hoisted and boats from HMS Alcide came to the rescue, but the gun crews remained at their stations and continued firing until the last possible minute before they were taken off. Shortly afterwards the ship succumbed to the flames and sank.

Nelson’s shore batteries were equally ineffectual, being sited at too great a distance from the French fortifications, and his cannonade did not advance the siege by so much as one day.

Despite these setbacks, the siege of Bastia has entered national myth as an occasion when Nelson showed resolute military commanders how to reduce a fortress, ‘We are few but of the right sort,’ said Nelson of his men and commended the soldiers under his command for ‘unexampled zeal’.

Just a few weeks after the fall of Bastia, Nelson was directing the bombardment of Calvi when a French cannon ball hit a nearby sandbag, which sprayed sand and debris into his right eye. Contrary to popular belief, he did not lose the eye, but did lose the sight from it.

Captain Hay Livingstone, who commanded the 30th’s Light Company on Corsica under Nelson in 1794. He lost his eye at Calvi in exactly the same manner as Nelson – from a rock splinter thrown up by a ricochet during the siege of Calvi.

Their strenuous efforts were apparently rewarded on 19 May 1794 by Bastia’s capitulation. Nelson claimed this as ‘the most glorious sight that an Englishman could bring about…. four thousand five hundred men laying down their arms to less than one thousand British soldiers who were serving as marines!’

Lord Hood, in scarcely less euphoric tones, wrote in his dispatch, ‘Major Brereton of the 30th Regiment and every officer and soldier serving under [Lieutenant-Colonel Villette’s] orders are justly entitled to my warmest acknowledgments. Their persevering ardour and desire to distinguish themselves cannot too highly be spoken of.’

But in retrospect it can be seen that Nelson’s vainglorious labours were entirely wasted, for, as Dundas and Sir John Moore [later of Corunna fame, who had brought reinforcements from Gibraltar] had predicted, Bastia eventually succumbed to blockade-induced starvation, and the main effect of the furious two-week bombardment was to deprive the fleet of much needed powder and shot and even more valuable lives.

A visit to the French positions after their surrender confirmed Moore in his opinion that the military advice had indeed been sound; ‘Upon the whole I am convinced that Bastia with our force could only be taken by famine. The land attack made by Lord Hood, though he will gain credit for it at home, was absurd to a degree. Three times his number could not have penetrated from that quarter. He never advanced one inch. If he had he must have been cut up. The distance of his post, together with the unaccountable want of enterprise in the enemy, saved his troops from destruction.’

Whilst this evidence casts something of a shadow on the myth of Nelson at Bastia, it does not detract from the gallantry of those who fought under his inspirational command on this occasion, and the Regiment has ever since taken great pride in its association with Britain’s greatest naval hero. Annually in October, a representative from today’s Duke of Lancaster’s Regiment, as the successor of the old 30th, takes part in the naval parade to commemorate the Battle of Trafalgar, and lays a wreath at the foot of his monument in Trafalgar Square. It is simply inscribed ‘BASTIA 1794’.